Copenhagen: 100 per cent renewable gas by 2025

3 January 2020

Heat and the city

22 December 2020Biofuels: The UK’s approach

Senior Policy Advisor of Low Carbon Fuels at the UK’s Department for Transport (DfT), Charlotte Stead discusses the direction of travel for advanced biofuels for transport in the UK.

Speaking in early 2020, Stead highlighted that in the UK less than 5 per cent of the 450,000 litres of fuel supplied to transport companies is biofuel, however, the Government has set a target to increase this level to 12.4 per cent by 2032.

The desire to progress the use of advanced biofuels in the hard to decarbonise sectors, such as transport, lies in the understanding of the potential benefits of greenhouse gas emission savings and that advanced biofuels avoid displacement effects when used to produce transport fuel, explains Stead.

Currently, the UK primarily uses waste feedstock for transport biofuel and has in recent years been moving away from the use of crops. This has been hastened by the introduction of a crop cap, aiming to reduce plant-based renewable fuels down to 2 per cent by 2032.

However, the majority of the UK’s wastefeed stock (47 per cent) comes from cooking oil, highlighting that advanced biofuels are not yet emerging at pace.

Stead explains that this is largely due to two major challenges. The first is the cost associated with producing advanced low carbon fuels, which historically arises caution in investors. The second is a question of feedstock availability. As the harder to decarbonise sectors increase their use of advanced biofuels, it’s likely that they will find themselves in competition for feedstock with other sectors. Additionally, Stead explains, it’s not simply the UK where there is an increased demand for feedstock, but demand for advanced biofuels has increased worldwide.

Explaining how the UK is addressing these challenges, Stead highlights that as of 2019, the UK has a target for development fuel, intended to stimulate the production of advanced renewable fuels and aimed at modes within the transport sector recognised as difficult to decarbonise including aviation and heavy goods vehicles.

It is also recognised that growth of the domestic industry of development fuels will have an economic benefit, given estimates that the global market is set to be valued at around £15 billion by 2030.

From 1 January 2019, the UK have made available Renewable Transport Fuel Certificates (dRTFCs) which allow for earnings to be made of up to £1.60/litre for development fuels and up to £0.30/litre for general fuels.

“This is recognising that the development fuels are much more expensive and that’s why they have a higher value,” explains Stead.

Another tool utilised by the UK Government is competitions. In 2014 the UK launched its Advanced Biofuels Demonstration Competition (ABDC) which made available £25 million (private sector matched capital funding) to companies to demonstrate waste to fuel technologies. “Specifically the competition sought to attract significant private sector investment, see first-of-a-kind biofuel plants built, support the development of the UK-based advanced biofuels industry and contribute to commercial waste based fuels that could offer significant carbon savings up to 95 per cent relative to fossil fuels,” Stead explains.

The competition is now in its final stages with a plant being built in Teeside where a company plans to create cellulosic ethanol from forestry residues and another in Swindon, where biomethane will be produced from municipal and wood waste.

The UK also launched a second competition named the Future Fuels for Flight and Freight Competition (F4C) in April 2017. The competition provided £22 million to “help construct novel, advanced low carbon fuel plants” in the UK by 2021. Projects were required to produce fuels from waste and offer an end product with greater than 70 per cent greenhouse gas savings compared to conventional fuels.

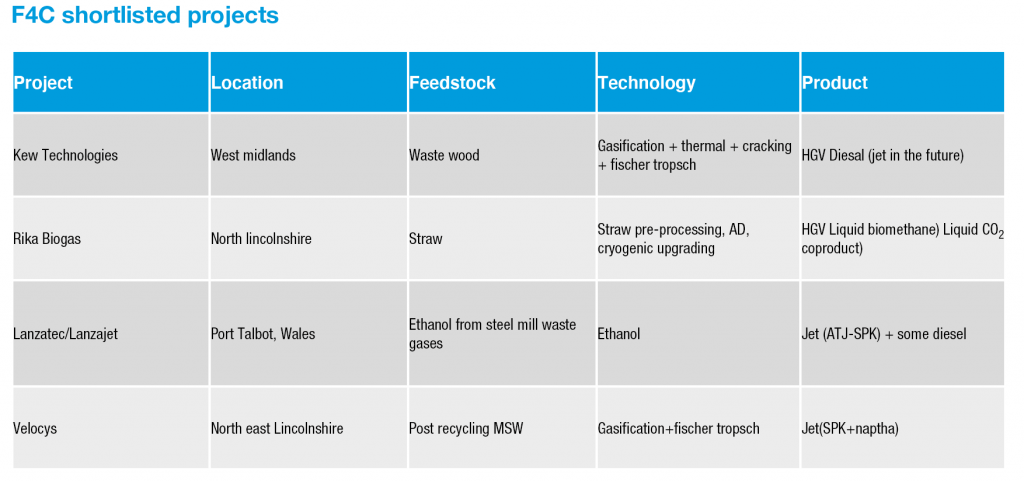

Stead explains that 28 projects entered for the first stage (2017-19) of the competition with seven projects sharing a £2 million grant pot to support preliminary project work. In 2019, four projects were shortlisted for the final stage with £20 million of funding made available. Two of the projects focus on aviation fuel while the other two focus on HGV fuels.

Turning back to the question of feedstock availability, Stead outlines that the UK Government are currently investigating the potential of recycled carbon fuels (RCF), which are transport fuels made from fossil derived wastes that are not suitable for reuse or recycling, or cannot be avoided.

The UK does not currently support these under the RTFO but recognises that there is potential greenhouse gas savings.

“We are exploring the greenhouse gas benefits of using them to produce fuels instead of how they are currently disposed,” says Stead. The pathways for RCF are varied and include the likes of incineration, cement Kilns, landfill, combined heat and power and heat.

“We are exploring the greenhouse gas benefits of using them to produce fuels instead of how they are currently disposed.”

“These are known as counterfactuals and each counterfactual will have a different level of greenhouse gas savings. One of the things we are exploring is which counterfactual should we be using RCF’s from,” she adds.

Stead explains that the Department for Transport has commissioned two reports on sustainability risks of RCFs and hosted RCF workshops in 2018 and 2019. Additionally, the Department has engaged with numerous RCF producers/potential producers in order to understand their process and the feedstocks used, as well as working closely with other government departments, making sure that there is alignment so as not to displace waste being used elsewhere.

Looking to the future Stead explains that the Department’s biofuel policy focusses on waste, which is demonstrated by current competitions, the crop cap, the introduction of development fuel sub targets and the double rewarding of feedstocks.

However, challenges remain in the face of rising targets across the EU and beyond which raises questions on whether enough sustainable material available and how low carbon fuels can be transitioned to difficult to decarbonise sectors.

“Our recommendation is that we need to diversify the feedstocks and unlock the more difficult to process ones,” concludes Stead.