Biofuels: The UK’s approach

21 December 2020

Energy storage and the grid

2 January 2021Heat and the city

Janette Webb, Co-Director of UK Energy Research Centre and Professor of Sociology of Organisations, Edinburgh University discusses the lack of progress on the decarbonisation of heat in Great Britain and its impact on net zero carbon ambitions.

The UK Government has set a net zero carbon target for 2050 and more ambitiously, the Scottish Government aims to reach the same goal by 2045. However, as Webb explains “minimal progress” on the decarbonisation of heat raises serious questions around how realistic these ambitions are with major social and political questions yet to be answered.

Webb, whose research has informed both the UK and Scottish Government policy on heat, highlights that Ireland’s position as a laggard on heat in relation to other EU countries is not unique when compared to its neighbouring countries of England, Scotland and Wales.

“Many around these parts are doing much the same and performing rather poorly on that conversion of high carbon heat into lower carbon or renewable heating systems,” she states. “We know this is something that is essential to meeting greenhouse gas targets but it is an area where we are making very little progress and where there aren’t straightforward answers.”

In Britain, people are very wedded to their gas heating systems so there has to be in place very clear quality assurance advisory, public standards, security/safety and open access evaluation of some of those bigger demonstrators that are beginning to come around in order to get the societal momentum that we need behind it.

In its 2019 report the UK Committee on Climate Change commented that: “Over 10 years after the Climate Change Act was passed, there is still no serious plan for decarbonising UK heating systems and no large-scale trials have begun for either heat pumps or hydrogen.”

The scale of the challenge has been acknowledged by the UK Government. The Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) stated in 2018 in relation to the decarbonisation of heat: “Change of this scale and breadth will require a level of coordination beyond most public policy change programmes.”

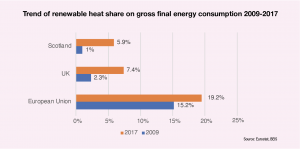

However, Webb believes that even this might be an understatement. In 2017, the European Union had a 19.5 per cent of renewable heat share in gross final energy consumption compared to 7.4 per cent for the UK and 5.9 per cent for Scotland.

Webb outlines a “cluttered landscape” in respect to heat policy across Britain including ambitious declarations by local authorities and city regional authorities, although these bodies have few powers and resources at their command to enable them to act “in a concerted and systematic fashion on the climate emergency”.

Part of Webb’s work of late has been trying to establish the role of local and regional governments in the decarbonisation of heat, recognising that a number of authorities have ambitious plans to be carbon neutral or carbon negative, yet continue to be heavily dependent on burning fossil fuel for heat.

Webb has drawn comparisons between England/UK Government policy and Scottish policy in terms of progressing decarbonisation of heat. Heat policy is devolved in Scotland, but in practice the devolution arrangement is complicated, with some levers such as building regulations being fully devolved, and others such as fuel standards and specifications, and energy market regulation, being fully reserved.

Webb outlines that current policies mainly overlap more than they diverge. However, in recent years the Scottish Government, while advocating for greater devolution of powers, has been active in developing not just heat policy but system-wide policies, including around local energy planning and zoning for different heat solutions.

However, the elephant in the room in relation to policy for decarbonising heat is the current gas infrastructure. Most of the heat in buildings and for industrial use across Britain comes from the highly developed gas grid that was built under public ownership and then privatised in the 1990s.

“Over a lot of the cluttered policy picture lies that question about what is the future of the gas grid and that is a question that really only can be answered by the UK Government because it is a reserved matter. Of course, underlying a lot of this is to what extent are we going to decarbonise the current gas grid?”

Addressing costs and how those costs will be shared is not one that ministers are keen to face up to, says Webb.

Turning back to policy comparison, Webb says that in England, the UK Government’s Clean Growth Strategy has tried to use liberalised market competition and market instruments to meet carbon reduction, and climate protection, targets. This includes feed in tariffs and subsidy schemes of various forms, often with limited life spans. The Renewable Heat Incentive (RHI), which ends next year and for which no equivalent replacement has been identified, is really the only scheme now supporting the market in renewable heat.

“The idea there was that the solutions would be led by the market. That the Government and the public would allow the market to discover the most cost effective solutions, but really there is still no clarity on the extent to which localised or regionalised market led solutions are emerging and emerging at the pace needed.

“What we have on the English side is a number of initiatives that are running without an obvious future route to a comprehensive solution or framework. So, we have initiatives such as the five local energy hubs which aim to develop project pipelines attractive to investors for a more decentralised system, where you could have different decisions about clean heat solutions in different places. The Hubs however work across very large areas and have very limited resources.”

Webb points to a possible exception to market-led thinking in the 2016 announcement by Treasury to invest £320 million in heat network development. This was renamed the Green Heat Networks Fund in the spring 2020 budget. The scheme remains the largest capital sum ever to be considered for heat network investments by the UK Government and applies only to England and Wales.

“Of all of those policies around market-led solutions for the future of heat, there is that one exception where there is recognition that there is scope to address a significant part of the problem through the development of new heat network infrastructure. However, it’s very hard to do that when you have a highly dominant and cost-effective gas industry meeting the majority of heating and hot water demand.”

In Scotland, however, the direction of travel has been towards a more managed market and a more partnership-thinking approach. In Scottish policy, terms such as planning, community and social inclusion are frequently used alongside the likes of market and competition.

“Some of the major issues on the Scottish side, apart from questions around social justice, concern the future of the oil and gas sector, which remains a massive contributor to the economy and employment, and what might take its place in a just transition. Also though, is the question around how to use less energy, because part of the thinking always has been that these solutions around heat, and I think this is true across the UK, is not to have any waste.”

In Scotland, a push towards a zero waste heat solution saw government identify buildings as a national infrastructure priority. In 2015, the Scottish Government opted to plan in various ways, primarily through cross sector partnerships, to retrofit the entire building stock to a much higher energy performance standard by 2040.

The Energy Efficient Scotland programme saw a series of pilot projects led by local authorities and gave prominence to planning at local and regional scale for a future net zero carbon building stock. The first phase of the scheme called for area-based initiatives to retrofit buildings, while the second phase did this again, but focusing on home owners and on detailed local heat and energy efficiency strategies (LHEES), which have become one of the key policy instruments in Scotland for decarbonising heat and improving the energy performance of building stock.

“It’s been really interesting evaluating those projects to see how difficult it is to organise the societal co-ordination, collaboration and consent around this kind of programme and I don’t think we’ve got very far yet,” says Webb.

“However, in that Energy Efficient Scotland programme, which is core to the net zero carbon heat target, is a national policy framework which envisages a more planned solution. This would mean local governments managing area-based advice and delivery services with business and third sector partners, supported by a national system to coordinate specialist legal, technical and procurement services, and funding, and to review progress.”

Webb explains that this localised approach is also being utilised to address the Scottish framework’s goal of resolving fuel poverty and ensuring that any transition does not exacerbate existing vulnerability problems.

A localised heat and energy efficiency solution aims to do this through costed and comprehensive area-based plans for decarbonising heating, including through the likes of zoning areas where district heat would be cost effective and identifying other areas where stand-alone heat pumps might be best. The ambition is for such schemes, in part, to be self-funded, however, as Webb explains, a viable route from what exists currently to full decarbonisation of heat is not clear.

Outlining a to-do list for the UK and Scottish governments, Webb states:

“I think it’s fair to say that right across Britain, a net zero carbon future for heating systems is just about on the policy horizon. There is a mix of ideas and debate on the extent to which markets can solve this without very significant public intervention and planning.

“I believe there are four interconnected themes from a social science perspective on how to solve that question. The first is the need for a working consensus on ‘what and how’. We’ve seen in our research the difficulties of getting the necessary cross-sector collaboration and co-ordination when regulation does not mandate it. Steps have been taken in England, Scotland and Wales to develop a cross-sector collaborative system on a voluntary basis, but where is that working? It’s not working anywhere terribly well, I would suggest.

“I think it’s fair to say that right across Britain, a net zero carbon future for heating systems is just about on the policy horizon.”

“Secondly, there is a need for clarity over who owns what problems and of course, the big question of who will pay. To what extent should infrastructure costs be socialised, given differential rates and forms of benefit in different places?

“Thirdly, some of the key starting points are around building stock renovation and retrofit based on clear policy targets all over Britain, but there has been rather slow progress. There has been progress towards better energy efficiency standards but we don’t have good subsidy schemes in place at present. We have loan schemes, but there is no requirement on most property owners to make use of those loans schemes and we’ve seen a big reduction in public finance for energy efficiency retrofit in England.

“Fourthly, we need to build public trust. To do this, we need some large-scale whole system demonstrators. We need to be able to view projects in a public setting, with open access evaluation. Additionally, we need to see how well hydrogen conversion of the gas grid can work and how the costs and benefits would be distributed between different groups.

“In Britain, people are very wedded to their gas heating systems so there has to be in place very clear quality assurance advisory, public standards, security/safety and open access evaluation of some of those bigger demonstrators that are beginning to come around in order to get the societal momentum that we need behind it.”