Decarbonising your business: Where do you start?

29 April 2021Renewable energy: The need for public buy-in

29 April 2021Pathways to the 2030 renewable electricity target

Fully engaging citizens while also seeking to rapidly increase the levels of renewable electricity generation out to 2030 presents the greatest challenge to ambitions, believes Director of the national SFI MaREI Centre, Brian Ó Gallachóir.

Highlighting renewable electricity as a success story for Ireland and an area primed for continued growth and development, Ó Gallachóir is quick to point out that while this is necessary it is not sufficient to deliver the overall goal of decarbonisation of energy use.

Currently, while one-third of our electricity is from renewable sources, only 11 per cent of overall energy use is from renewables, meaning that some 90 per cent still originates from fossil fuels.

“We are world-leading in terms of what EirGrid is doing in integrating the levels of variable renewable electricity into a synchronous AC power system, but unless we address the areas of heat and transport, we will remain a laggard in emissions reduction and in renewable energy achievement overall because electricity represents just 20 per cent of our energy use,” he says.

Ó Gallachóir highlights that while Ireland is well on course to meet its 40 per cent renewable electricity target, this will represent just 8 per cent of overall energy use coming from renewable electricity and recommends a shift in policy focus to see the renewable energy level increased.

“Energy efficiency and electrification (EVs and heat pumps) will help but I think the focus in the heat and transport sectors has to move beyond efficiency and electrification and into renewable fuels,” he states.

Turning to the Government’s ambition for Ireland to meet a target of at least 70 per cent electricity supply from renewables by 2030, Ó Gallachóir points to three key questions for consideration: How much? How fast? And how difficult?

How much?

On how much, Ó Gallachóir points out that while the 70 per cent target is set and clear, the amount of renewable electricity needed to reach 70 per cent is less clear, because the volume of electricity that will be used in 2030 is uncertain.

Highlighting the possible variations of electricity use by 2030, the academic points to EirGrid’s Tomorrow’s Energy Scenarios report, which offers three different scenarios of electricity use in 2030. Interestingly, all three scenarios reflect a significant uplift from the 2020 figure of 30 TWh to an estimated low of 37 TWh, medium of 41 TWh and a high of 45 TWh. The highest of these reflects a potential 50 per cent increase in electricity consumption over the next decade.

MaREI’s own research on the Net Zero CO2 emissions pathways to 2050 also points to a significant increase in demand in electricity by 2030 of 42 TWh and an even more significant jump to 75 TWh by 2050.

“What these projections highlight is that the amounts are not certain by any means. These step changes in electricity demand are very significant but in order to understand what 70 per cent RES-E means, we need to understand what it will be 70 per cent of,” he explains.

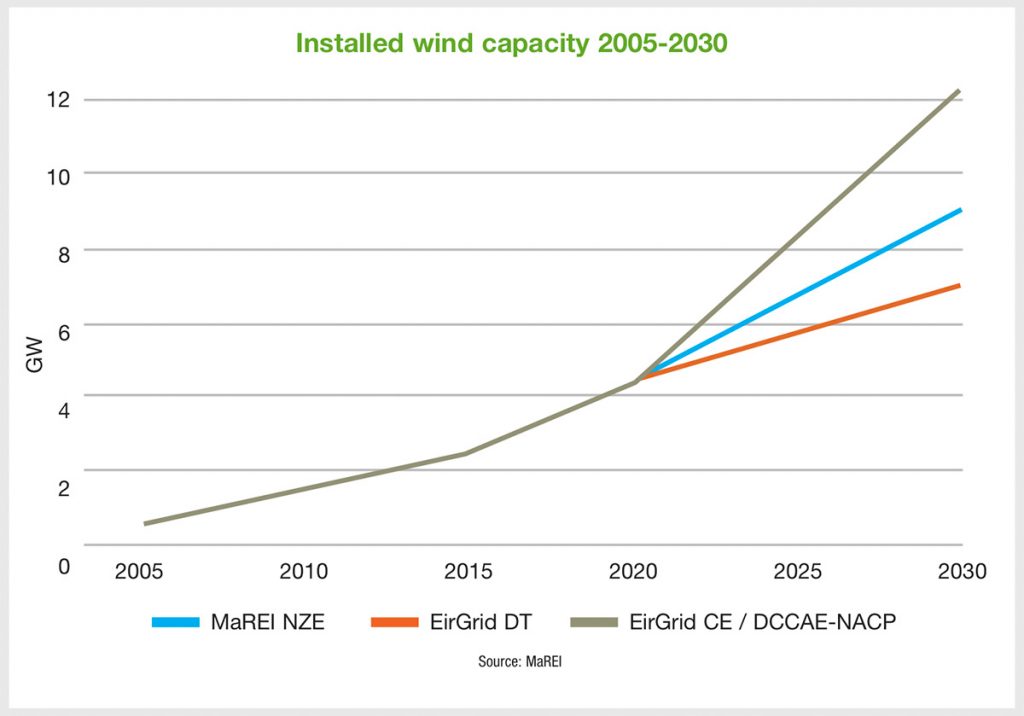

Taking MaREI’s analysis of demand at 42 TWh by 2030, this particular scenario suggests a requirement of 8.5GW from offshore and onshore wind combined and a growth of solar from a low base to 1.2GW. “Whether the 11.7GW of renewable electricity will translate into 70 per cent RES-E by 2030 depends on the amount of electricity required by 2030,” explains Ó Gallachóir.

How fast?

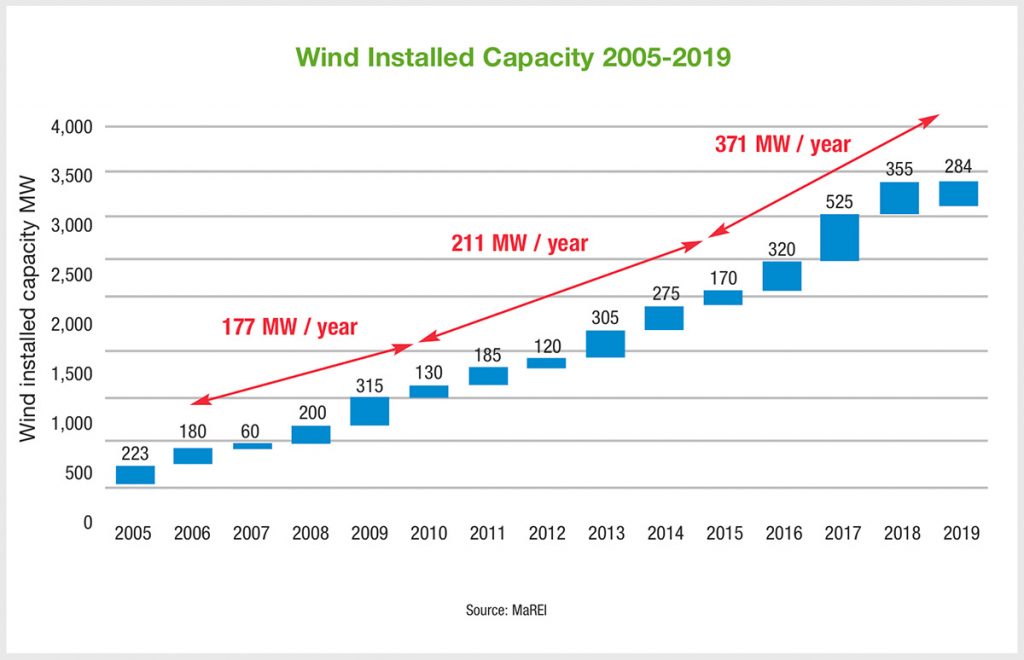

Ó Gallachóir highlights a significant recent growth in the average additional installed capacity. The 371MW per year on average of additional installed wind capacity over the past five years is significantly above the 211MW per year recorded between 2010 to 2015 and effectively representing a doubling of the levels added in the period from 2005 to 2010.

However, despite this growth, driven by onshore wind, the Climate Action Plan’s projection of 732MW per annum by 2030 will require an even greater level of growth than has already been realised. Breaking it down further into onshore and offshore wind, Ó Gallachóir suggests that the jump in onshore capacity required from 370MW per year to 414MW is not a huge increase. However, the main challenge will lie in increasing the installed capacity of offshore wind energy from its much lower staring point of 25MW currently.

How difficult?

Ó Gallachóir categorises the challenges in meeting the 2030 target into three specific areas: technical; financial; and ownership.

On the technical challenges, he points to EirGrid’s ambition to reach a system non-synchronous penetration (SNSP) level of 75 per cent by Q4 2019, which would be a further world-leading feat. The academic explains that to achieve 70 per cent RES-E on average would require the accommodation of 95 per cent variable RES-E at any one time, something which hasn’t been done before.

“There was a suggestion that an all-island grid study be repeated in this new context. I believe that is a good idea because we are again going into unchartered territory. We have the ambition and we’re moving towards it but we don’t know what the answers are,” he states.

Regarding financial challenges, Ó Gallachóir is of the opinion that restrictions in this area may be less significant than in others. While many have voiced concerns around the potential cost associated with reaching the 2030 target, the academic sees signs that Ireland could position itself well to raise funds. It’s estimated that an increase of some 11-12GW would require €15 to €20 billion of investment. “The discussions seem to suggest that Ireland is viewed as an okay place to invest and that with renewable growth represents investment opportunities,” he adds.

However, the largest challenge Ó Gallachóir identifies is that around community acceptance, participation and in particular the challenges associated with the pace of change required. One of the Department’s policy responses has been a move to engage citizens and communities in different ways than before, including through the likes of energy communities and citizen investment opportunities.

“On citizen engagement, the one thing that is very clear is that it takes time,” explains Ó Gallachóir. “It’s a very necessary and evolutionary process but that time challenge appears juxtaposed with the urgency to accelerate generation development. It’s citizens who are campaigning for climate action, who are sometimes protesting against infrastructure and who are forming energy communities and I don’t think there is enough focus or understanding of these dynamics.”

The Government’s RESS support scheme, which delivers as enabling framework for community participation through the provision of pathways and supports for communities to participate in renewable energy projects is a “positive step” from a policy perspective, he says. Similarly, the Community Benefit Fund, which must mandatorily be provided by all projects successful in a RESS auction is another policy response to engage citizens but, as Ó Gallachóir points out: “Getting the correct levels of citizen engagement and participation is going to be very challenging. It’s certainly very challenging to the industry in the context of time urgency.”

Concluding, Ó Gallachóir says that while the technical elements of delivering on the 2030 target are very challenging, expertise in the area stands to benefit Ireland. The financial challenges, he believes, are not insurmountable but adds: “I think the ownership piece and the engagement with citizens has been given the least attention compared to the others and I think it is where most attention is required.”